A House of Firsts

Ruinart claims many ‘firsts,’ but the most important came in 1729 when Nicolas Ruinart opened a ledger for the world’s first ‘wine with bubbles,’ thus creating the first champagne house in the world.

Although a draper by trade, Nicolas Ruinart took inspiration from his uncle Thierry (a Benedictine monk and contemporary of Dom Pérignon) and pursued his vision to provide ‘bubbling wine’ to young aristocrats of the worldly society during the Enlightenment period of the eighteenth century.

What started out as mere business gifts to important cloth customers soon became a steady stream of income for Nicolas Ruinart. By 1735 the ‘bubbling wine’ grew so popular that Nicolas Ruinart withdrew from fabric sales and focused solely on the production of champagne. In 1730, Ruinart sold 170 bottles, but business quickly ticked up with 3,000 bottles sold in 1731 and 36,000 sold by 1761. Intellectuals and aristocrats of the Enlightenment period enjoyed stimulating tableside conversations that included fine wines and other exotic delicacies such as champagne. The cultural revolution of the eighteenth century provided fertile ground for Ruinart to expand production and distribution.

Company records dating back to 1764 verify that Ruinart had also become the first producer of rosé champagne. Around this same time, exports of Ruinart expanded to aristocracy in Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, England, Ireland, Ukraine and America. As Ruinart became ever more successful and well-known, storage space for the champagne grew scarce. In 1768, Claude Ruinart, son of Nicolas, became the first champagne producer to purchase five miles of subterranean Gallo-Roman chalk quarries. These ancient quarries, dug out under the city of Reims, consist of a mesmerizing labyrinth of chalk chambers, sometimes as deep as 125 feet. Claude Ruinart understood the potential of these pits with their thermal stability, absence of vibration and perfect humidity levels.

The chalk quarries represent the connection of past, present and future for the champagne house.

Known as crayères, these subterranean chalk caverns now shelter champagne as it undergoes near-perfect maturation in bottle. However, throughout their history the crayères served as places of refuge during conflict, sites for opulent parties, and now – prearranged guided tours. The chalk quarries represent the connection of past, present and future for the champagne house.

In 1931, the crayères were granted historical monument status by the then Ministry of Education and Arts. Today, they are part of the Champagne Hillsides, Houses and Cellars UNESCO World Heritage Site. Thousands of crates of bottles line the dimly-lit walls, resting at a constant 51 degrees Fahrenheit. Many of them are going through the process of ‘remuage,’ which involves a gradual turning and inversion to bring the sediment from the yeast fermentation into the bottle’s neck to be removed before the aging starts. Some champagnes, like the Dom Ruinart, age for nine to twelve years in the crayères.

After the Great Depression, followed by consecutive World Wars, Ruinart struggled to find its footing. By 1946, only 10,000 bottles were left in stock. German soldiers looted the stores of champagne – explaining why no bottles prior to 1945 exist. After hundreds of years of success, the world’s first champagne house looked to be on the brink of extinction. However, in 1946 a family member took over and began to rebuild the brand from scratch. This change in leadership coincides with Ruinart’s focus on Chardonnay, which today characterizes Ruinart champagnes.

Ruinart now finds itself within the LVMH luxury group alongside some of the most well-known and sought-after brands in the world. The world’s oldest champagne house continues to age well, selling an estimated three million bottles per year.

The champagne house made headlines in 1896 when Andre Ruinart commissioned famous Czech illustrator Alphons Mucha to create the very first advertisement for champagne.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution was underway in Paris; the city glittered with celebration and colorful posters could be seen everywhere. Andre Ruinart realized that to stand out, an advertisement had to be distinctive. At the time, a poster for the Greek melodrama “Gismonda” had raised quite a stir. With delicate floral motifs and gold coloring, Mucha’s style possessed unmistakable, ethereal charm. His uncluttered compositions with fluid movement, soft colors, and graceful figures were signals of the celebratory atmosphere in Paris.

The advertisement commissioned for Ruinart featured a goddess-like woman raising a bubbling glass of champagne, held more like a torch. The poster inspired celebration and served as an allegory for the French art of living. Mucha’s work possessed a timeless feel and was reinvented and reused by Ruinart until 1930. Mucha’s larger body of work proved to be of great influence in the Art Nouveau movement.

Mucha began Ruinart’s longstanding collaboration with artists that continues to this day. Now, Ruinart gives carte blanche to contemporary artists each year to share their vision of the famous champagne house. Aside from welcoming new artists to Reims every year, Ruinart provides support to more than 35 art fairs in fifteen countries.

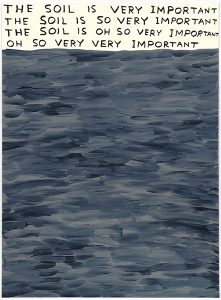

British artist David Shrigley shines a new light upon Ruinart in 2020. Shrigley follows in the footsteps of Liu Bolin (2018) and Vik Muniz (2019) but provides his own unique take across an ensemble of 36 artworks, three neons, two ceramics, and 30 limited-edition champagne boxes. His quirky and uncompromising humor works across an extensive range of media including sculpture, large-scale installation, animation, painting, photography and music. In his collection for Ruinart, he prods the viewer to think deeper about what lurks inside the bottle.

“When making art on the subject of champagne production: one must make several visits to the champagne region; one must visit the crayères and the vineyards and the production facilities; and one must ask questions of the people who work there and listen very carefully to what they say. And most importantly you must drink some champagne,” Shrigley explained.

Contemporary artist David Shrigley set out to answer the question: what hides behind the developmental process of this exceptional beverage?

Shrigley roamed among the vines, explored the cellars and noted each individual expression and gesture. The rituals and customs behind the creation of champagne slowly surrendered their secrets, which he attempts to reveal in his work. Just like the intellectuals of the Enlightenment era that raised questions about the art of living, so too does Shrigley’s work provoke interesting conversations about nature and the wine-making process. His work forces the viewer to remain mindful of the day-to-day environmental challenges of wine production.

During his residence with Ruinart, Shrigley created one hundred drawings, titled “Unconventional Bubbles.” Rudimentary but unmistakable line drawings paired with ironic and sometimes absurd statements or questions challenge a viewer to pay closer attention to what they consume in a bottle. The drawings operate with a level of ironic humor, but nonetheless, they evoke a keen awareness. Shrigley’s glazed ceramics question the difference in perception between the placid container and the evocative content.

In his limited-edition jeroboam size of Blanc de Blancs, Shrigley designed only 30 boxes, all numbered and signed personally. The black and white boxes contain statements that reveal the hidden side of wine production, exposing the relationship with nature. By proclaiming, “Worms make the wine; Bees make the wine; Humans make the wine; The air makes the wine,” he forces a consumer to think about opposites that complement each other in order to unite in a bottle of champagne. The large jeroboam size allows exceptional capacity for preservation and the expression of more complexity and aromatic variety.

Shrigley’s goal of bridging the gap between production and consumption echoes Ruinart’s longstanding drive to create a product that can be admired and cherished as a true work of art. He joins a long list of artists allowed to illuminate the art of champagne production.

Shrigley’s unmistakable line art is used to observe surroundings with incomparable irony and absurdity to challenge our perceptions

Related Stories

Planworthy Journeys with KEY.co in 2024

Allow Jet Linx and our Elevated Lifestyle partner KEY.co to take you on a planworthy journey. Adventure awaits with KEY.co’s 2024 top travel destinations and custom-crafted itineraries.

READ MORE

Elevated Lifestyle Holiday Gift Guide

Elevate your gift-giving this year with our annual Elevated Lifestyle Holiday Gift Guide.

READ MORE

A Seamless Journey Awaits You: Meet Our Elevated Lifestyle Transportation Partners

We know that every step of your journey matters, and our ground transportation partners ensure that every mile traveled is nothing short of extraordinary.

READ MORE

Related Stories

Planworthy Journeys with KEY.co in 2024

Allow Jet Linx and our Elevated Lifestyle partner KEY.co to take you on a planworthy journey. Adventure awaits with KEY.co’s 2024 top travel destinations and custom-crafted itineraries.

READ MORE

Elevated Lifestyle Holiday Gift Guide

Elevate your gift-giving this year with our annual Elevated Lifestyle Holiday Gift Guide.

READ MORE

A Seamless Journey Awaits You: Meet Our Elevated Lifestyle Transportation Partners

We know that every step of your journey matters, and our ground transportation partners ensure that every mile traveled is nothing short of extraordinary.

READ MORE

Contact Us